Our Earliest Days

(The following material comes from the first chapters of the book “Strong Man Lodge No.45 – The First 275 Years”, by Burt Edwards and Bernard Williamson, with additional material collected from original sources by Nigel Woolfenden, our Lodge Historian)

The Origins of Freemasonry in England

Although Freemasonry is the largest and one of the oldest fraternal organisations in the world, with lodges in almost every democratic country, its precise origins are somewhat lost in time. What we know is that it derived from the lodges of medieval stonemasons, of which we have records and documents going all the way back to a time between the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th.

A lodge, or “loge”, was simply a site hut for the men building a castle, or cathedral, or other large stone edifice. Here the “operatives” quaffed porter (dark beer) or mead and ate boiled meat or fish to satisfy noontime hunger during their long hours of labour. Trade secrets were exchanged and apprentices quizzed on their proficiency. It was here that the mysteries and secrets of the Master Mason’s skills were passed on, orally, with a guardian at the door to keep off intruders or unskilled labourers from entry. The stonemason’s art was passed on only to suitable apprentices and then up the skill-levels to the experienced Masons who were able to do the splending work which has survived for centuries.

Lodges also acted as a form of early welfare system, providing assistance to members in need and, if they passed away, even to their widows.

These operative lodges flourished through the 16th century but things began to change in the mid-17th: an intense urbanisation in London and other cities led to a strong demand for stonemasons, which had to be imported from the provinces. The demand further increased when the bubonic plague wiped out many skilled workers in 1665, and increased even more when in 1666 London was ravaged by the Great Fire: workers could easily find employment without being members of a lodge (and therefore without paying the associated fee), and the previously close-knit groups of local men were no more. Thus, the long-established lodges of operative Masons, with their hierarchy, progressive training and protection of job skills, were thrown into disarray. Skilled workers in other trades who were not operative Masons, but rather speculative, began to be accepted into lodges, a reluctant but necessary step to boost the parlous state of the benevolent funds. This spelled the end of operative Masons’ lodges, and generated the earliest form of modern Freemasonry. In the friendly discussions among members, regulations of the stonemasons’ trade were gradually replaced by more philosophical subjects, and the proper methods for erecting a beautiful edifice became a metaphor for the path to follow in order to become a better person. The tenets of brotherly love and mutual support acquired a more universal meaning, as lodges opened up not only to men of all professions, but also of all races, nationalities and creeds.

It soon proved more practical to conduct meetings in taverns, which at the time tended to be tiny, and either clean and simple or squalid and uncomfortable. Many businessmen and traders spent as much time at the tavern as at their homes and offices, and a handshake over a pot of porter often clinched a deal. Apart from food, the main delights of Masonic refreshment were smoking, drinking and singing. Long clay churchwarden pipes were supplied free by the landlord and punch, wine or porter was quaffed from a large bowl common to all, with much inpromptu singing. As all this occurred through actual Lodge proceedings, not afterwards, it is little wonder that our ancient Minutes are difficult to read, as no scribe wished to be left out of the toasts and general festivity. Surely a different atmosphere if compared to modern Masonic meetings.

A private room for a lodge’s use was typically about 12ft square. Taverns were usually ordinary houses with a frontage of about 20 feet. Fifteen Members could mean overcrowding. The assembled Brethren, properly dressed, sat down around a table on which were candelabra and a large bowl of punch. Clay pipes were lit up and, as the evening progressed, food was delivered by the doorkeeper.

When Strong Man Lodge was officially constituted on February 2nd 1733, our meetings were probably very similar to the ones described above.

What’s in a Name?

With almost 300 years of history, we can proudly claim to be one of the oldest lodges in England and in the world. We were constituted in 1733 but various records show that we were meeting already since 1728, although not in an “official” capacity, meaning that we did not yet have a Warrant from the Grand Lodge.

The number 45 is somewhat misleading, as lodge numbers changed more than once in the 18th and 19th centuries, as they were re-allocated by the Grand Lodge as other lodges closed or merged. We were given No.110 in 1733, became No.98 in 1740, No.68 in 1755, and so on and so forth until we finally settled to No.45 in 1863. However, in a study made by Peter Vidler it is shown that if surviving lodges had been renumbered according to their age, we would be No.21 or No.22.

Originally, lodges were known by the name of their meeting place, which would have been an inn, a tavern, a coffee house or simply somebody’s house. As our lodge did not meet in the Strong Man Tavern until 1764, it is only then that have had our present name. Before that, we would have been referred to as “the men from the house on Labour-in-Vain Hill” or, when we moved to the Ship tavern, as “the lodge in the Ship Hermitage”. The reasons for moving from one place to another could vary quite considerably, but we know that at one time Strong Man Lodge voted to move from a tavern because the landlord was raising the price of a barrel of brandy by 2/6d (2 shillings and 6 pence, or a half crown).

Our present name must have been popular with the Brethren because we kept the name after we left the Strong Man Tavern, with no evidence of having used the name of other meeting places.

Strong Man Tavern was so named because its landlord, Thomas Topham, was a famous Londoner who performed extraordinary feats of strength. The son of a carpenter, he was born circa 1710 and, while we have no proof that he was a Mason, we do know that he kept company with Dr. John Theophilus Desaguliers, who was a member of the Royal Society, an experimental assistant to Sir Isaac Newton, and the 3rd Grand Master of the Premier Grand Lodge of England.

We know quite a bit of Thomas’ life: at only 24, he became the host of the Red Lion near the old hospital of St. Luke. This business failed, probably due to his inattention to the business side and the bad company he kept. The area, Moorfields, was the “gymnasium of our capital and the great resort of cudgellers, wrestlers, back sword players and boxers from all parts of the metropolis.”

In October 1733, Thomas demonstrated his feats at a Royal Society meeting, and they are documented in the Society’s library and in Dr. Desaguliers’ book “A Course In Experimental Physics”.

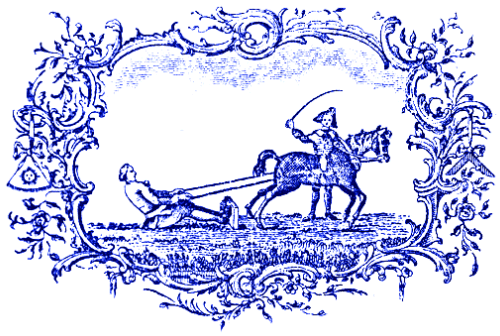

One of the first public exhibitions of his extraordinary strength was of pulling against a horse whilst lying on his back and placing his feet against the dwarf wall that divided upper from lower Moorfields, and this feat is what we have been using for a very long time in the emblem of our old lodge.

Dr. Desaguliers wrote in excruciating detail about many of Thomas’ feats of strength, and was convinced that if in the proper position he would have been able to pull against four horses.

Thomas’ fame allowed him to travel across England, Scotland and Ireland to show his extraordinary strength, and even Harry Houdini described his feats in his book “Miracle Mongers and Their Methods”.

Unfortunately, Thomas’ life came to a premature end in 1749 when one fateful day he came home and found his wife with another man. In a fit of rage he stabbed her, and then he retired to his bedroom where for the remorse he cut his throat with a razor. It took him three days to die in severe pain but his wife recovered from her wounds and continued to run the tavern.

And so ended the life of a very unusual man. Knowing about all this, it is not surprising that our Brethren, when they moved to the Strong Man Tavern in 1764, decided that they would like to be named after it. From then, we became the Strong Man Lodge and kept the name despite moves to many other taverns and inns.

It must have been a nice and friendly venue, because we remained at Strong Man Tavern until 1813, making it the third longest stay after Freemasons Hall (where we have been meeting since 1955) and the Holborn Restaurant, which we used from 1898 until 1954.

One Strong Man, Many Sea Captains

The reasons for moving from one place to the next could vary a lot: as already mentioned, the cost of drinks was sometimes a factor. The quality of food could be another. Other times, the increasing amount of members forced us to find more spacious venues. As far as we can tell from the records we were never evicted for annoying or riotous behaviour, although we know that we occasionally received complaints from neighbouring citizens about excessive noise of Brethren departing into the night. To our defence, it was far from a rare occurrence for London lodges.

Our very first meeting place was the Crown and Mitre, Labour-in-Vain Hill, Old Fish Street, directly south of St. Paul’s Cathedral, by Lambeth Hill. The sign issued by the brewer William Baggott showed two women trying to scrub a black man white, implying a labour in vain. With it, the brewer was defying the competition to produce ale as good as his, which suggest that the earliest members of our Lodge might have chosen the place for the quality of the drinks. Oddly enough, the same house was also known by another name, the Rummer and Mitre (a rummer was a large drinking glass shaped like a sundae glass).

We stayed at the Crown and Mitre for less than one year, and then we moved to the Ship Coffee House, near Hermitage Bridge, between Tower and Wapping. It was not the most renowned part of London, since “the tenements in St. Katherine’s precinct and off the highway teemed with vermin and smelt evil”. The area was popular with seamen and dockers, but also with criminals and prostitutes. Sanitation was non-existent.

The area might not have been the most elegant in London, but it had one clear advantage: plenty of sea captains and officers willing to join Freemasonry, and our Lodge made the most of it. We know that we had many of them among our members in that period, and that our Lodge was certainly chosen by the Merchant Navy as a favourite for membership as early as the mid 1740s, although it is difficult to know the precise numbers as not all Secretaries gave captains and officers their titles. There was obviously a very high turnover, with many members only being able to attend one or two meetings before having to set sail again.

Instead of meeting at a tavern we picked a coffee house, which was a far more respectable business. Coffee houses were becoming important meeting places and record show a thriving community in the area, with tallow chandlers, victuallers, bakers, bricklayers, and wig makers. In the City of London coffee houses played a significant role in the development of insurance, stockbroking and commodity trading.

We still have records from the those early years, as our Secretaries at the time seemed to take great care in keeping track of meetings and membership. Unfortunately our very first book of Minutes, covering the meetings from 1733 to 1760, was lost in a fire in the mid 18th century, but we have a Quarterage (subscription) Book starting from January 1749 which lists the names of each member and the amount paid per quarter, normally 6/6d (6 shillings and 6 pence). Elections were normally made in December and June, so changes often occurred every six months, and not every year as today.

Initially, Secretaries did not bother recording members’ profession and place of residence. The first instance of that happening is when a Bro Whiteway, described as a “Gentleman of Walthamstow in Essex”, was initiated on the 18th of June 1752.

Those Old, Old Chairs…

The Lodge has a number of valuable artefacts in its possession – our Tracing Boards are awesome, for instance – but none are so prized as its set of three wonderful mid-1700s chairs that our Worshipful Master and Wardens use on our yearly Installation night, and that can be otherwise seen at the museum at Freemasons Hall. They are believed to have been made by Thomas Chippendale but we are not sure about the exact date, although a reasonable estimate places them in the 1750s. What we do know is that they were far from cheap, but our Lodge could count on a steady income thanks to the constant influx of sea captains being initiated, and that is most likely what paid for these items, although a generous donation from some of the most affluent members cannot be ruled out. It is always a great pleasure, and one of our most beloved traditions, to use these chairs once every year. It is also quite a shock for the newly installed Worshipful Master, unless he happens to be a very tall person, to realise that his feet cannot reach the floor!

At the time we were meeting at the Samson and Lion, in Butchers Row, East Smithfield. The Ship by then was working as an inn, and it was probably too crowded for our liking. Meetings were twice a month, on the 1st and 3rd Thursdays, and this includes both actual ceremonies and rehearsal sessions.

Our first recorded 3rd Degree ceremony is on 17th of January 1760, although we can be confident that the lodge conferred that Degree before that date, and that we simply do not have the Minutes reporting it. However, we must not forget that in operative Masonry there were only two Degrees, Entered Apprentice and Fellow Craft, and that a Master Mason was simply a Fellow Craft who employed other Masons. Early speculative Masonry followed the same principle, and the trigradal system we practice today only appeared in the 1720s, when the First Degree was split in two and the Second Degree became the Third incorporating the Hiramic legend. This new system was probably adopted relatively quickly across lodges in England and it had become the standard by the time the rival Grand Lodge (the “Antients”) was founded in 1751.

On 18 August 1763 we have the first instance of a clergyman, some Rev Entick, becoming a member of our lodge. Exactly 5 years later, on 18 August 1768, we know that an Initiate failed to appear for the ceremony and therefore forfeited his deposit. A few months later, on 19 January 1769, we have the first known instance of a Candidate not being accepted by the lodge: Mr Simpson is “blackballed”.

The 1770s is the first decade when we have complete Minutes, and it is striking how closely the Lodge, by that time, mirrored our current practice: aprons, Past Master’s Jewels, a banner, summonses, certificates, tylers & even an organist are all mentioned. Although the ritual was obviously still quite different (the ritual took its current form following the union of the two Grand Lodges in 1813), current members would have felt quite at home at Strong Man Lodge back then!